Disagreement, Reimagined

John Hopkins' Dr. Ashley Rogers Berner on the importance of modeling "political tolerance".

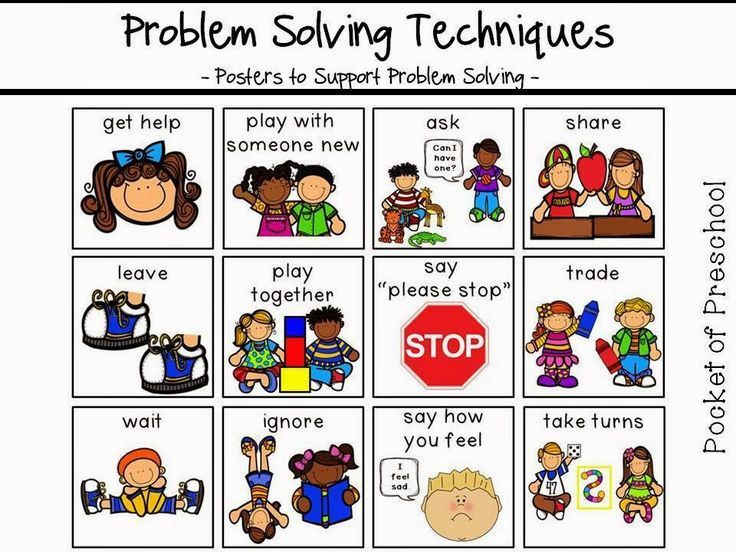

This week we took a cold plunge into the world of preschool tours. As someone who doesn’t remember much about early childhood, it’s the closest I’ve felt to time travel. Small wooden chairs and cubby holes and snack time. Thematically, parenthood (at least at this stage) feels like a daily reminder of principles often overlooked in adulthood, like listening and understanding; the notion of putting ourselves in someone else’s shoes; and respectful disagreement.

And it makes sense that we think about these things less and less. As we get older we develop an identity and a way of seeing ourselves and the world. The contours of our lives become more rigid. Our social circles, professional networks, even friendships gravitate towards ideological cohesion. Disagreements tend to become less invigorating and more uncomfortable.

In my work as an entertainment lawyer, disagreement is a sport and unlike me and real-life sports, I like winning. But in my personal life, I don’t want any part of it. I’ve always been a pacifist. A teacher once told my parents I’d probably become a diplomat, and diplomacy has served me well.

At the risk of sounding naive, I believe that getting uncomfortable isn’t always a bad thing. And in the context of civics, knowing that disagreement is an art form is different from understanding that it’s actually the lifeblood of a healthy democracy, and as parents, we’re responsible for the way we frame the art of disagreement between citizens. But where do we start?

I’m so excited to have Dr. Ashley Rogers Berner from Johns Hopkins back with a follow up to last fall’s post on building children’s political knowledge. Below, Dr. Berner shares fundamental tips for helping kids learn political tolerance, and in the process, reframing our ideas on disagreement. And be sure to check out Dr. Berner’s “Civics at Home” resource, linked below, for more tips - I’ve looked over many resources on this journey and it’s one of the best I’ve seen.

I’m so glad to be back with Civic EQ in the New Year. In November, Sarah and I wrote about how parents can build children’s political knowledge, or the specific content that democratic citizens should carry around with them. This time, we look at another critical piece of democratic formation: political tolerance.

“Political tolerance” isn’t a relativistic, “whatever” affect. On the contrary: it’s the capacity to hold strong views while, simultaneously, engaging respectfully with those who disagree.

We’re not born knowing how be politically tolerant. Believing something strongly and argue for it without diminishing others requires practice, effort, and role-modeling. As Bill Galston, one of my heroes in this space, observed in his elegant Anti-Pluralism (2018), “The desire to suppress speech and behavior one finds offensive is instinctive. Restraining oneself from doing so goes against the grain and requires training and indoctrination.”

So how do we help kids learn political tolerance? Classrooms should, but often don’t; news channels should, but often don’t, either. The good news is that research points toward factors that, if present throughout childhood, predict political tolerance in adulthood. For instance, being part of a school community with a clear, shared mission; routine engagement with different viewpoints; and coming of age in a politically competitive district all have positive civic effects. These findings can be translated into the routines of family life! Here’s how.

Explain the ethical claims that “live” in your family. All human institutions rest on norms and values. Families are no different, and that’s generally a good thing. Developmental psychologists emphasize the importance of early ethical stability in the development of children’s identities. Whether religious or secular, explicit or tacit, these norms inevitably include beliefs about politics, the just society, obligations towards other individuals and other nations (or not), etc. Our kids will inevitably learn from these sensibilities, even if they later modify or reject them. That’s okay.

Take time to explain why you favor certain politicians and policies over others, becoming more specific as your children grow older. The national issues can overwhelm our political bandwidth, but local issues are important, too. They’re accessible even while driving to piano lessons or baseball practice. For instance, what’s the difference between electric and gas fueled cars? Little kids can count how many they see of both kinds, and older ones can think through pros and cons to favoring one over the other. Or, do your kids have a favorite playground? If so, you could talk about the why and the how of shared public spaces - drawing on their own ideas about what it means to be in a community.

Introduce them to multiple perspectives. Young people need to encounter different ways of reasoning through tough issues! This is one of the missing pieces in American education that we can work on from home. I had an extreme experience of this growing up. My parents were well-educated conservatives who voted for Reagan and read Solzhenitsyn to us before middle school. They were also keen to introduce us to alternative views. I’ll never forget watching a refugee from the former Soviet Union get into verbal fisticuffs with a Marxist professor in our living room! This level of intensity isn’t necessary to key in to contrary opinions, thankfully. Do you have a good friend who disagrees with you politically? Invite your kids into a thoughtful conversation about things you both care about – and show how you would solve a known problem differently. Or pick an issue that your middle-schooler cares about, research both sides, and make best case for each. Invite friends and family into the mix via Zoom.

Model intellectual humility. It’s incredibly powerful to hear parents say, “I don’t know” and, “I haven’t made up my mind about that yet.” Or how about, “I have changed how I feel about that issue over time?” Having firm, well-informed opinions is great, and revisiting them over time is important, too! Giving ourselves, and our children, permission to change our minds based on new information, serves all of us well.

Of course, there are limits to the above based on children’s age and maturity, and with respect to the topic itself. “Multiple perspectives” need not include those of Holocaust deniers, nor do debates need to re-adjudicate the merits of, say, gender-based voting rights.

There are lots of resources to help jump-start controversial conversations in the family. Some of them can be found in this resource, Civics at Home, that my team developed before the last Presidential election.

Yes, political tolerance is in short supply right now. Yes, most of us – most Americans – feel “exhausted” at the thought of politics. But deliberating about important issues with people you trust, and letting your kids in on it, can be immensely rewarding. It is certainly beneficial. It can even be fun.